(Calvin’s Theology in Heinrich Bullingers “Helvetic Confessions”)

4.1 Need of a Pan-Helvetic Reformed Faith Concept

The Reformed tradition has its earliest roots in Switzerland with Zwingli and Heinrich Bullinger

(1504–1575), who established and systematized it after Zwingli’s death.25 Calvin (1509–1564),

its greatest representative and most influential exponent, he established Geneva as a model

Reformed city. In many respects, Geneva was the most important Protestant center in the

sixteenth century. This was not only because of the presence of Calvin, but also because Calvin

established a seminar to train and educate Reformers for all of Western Europe.

Amazingly—the town became the Protestant print capital of Europe, with more than thirty houses

publishing literature in various languages. Because of Zwingli’s premature death on the

battlefield, the fact that Bullinger works28 were not as easily accessible by the later Calvinist

tradition, and Calvin’s able work in systematizing Reformed Protestantism through his Institutes

of the Christian Religion, commentaries, sermons, and leadership, the terms Reformed and

Calvinism became virtually synonymous. Calvin himself preferred the word Reformed because he was opposed to having the movement called by his name. Bullinger, a staunch supporter for Zwingli and Reformed theology quickly established himself as the defender of the ecclesiological system developed by Zwingli, the promoter and supporter of Calvin's Reforms for French and English speaking Europe. Through Bullinger writing’s and especially the Helvetic Confessions, Calvinist theology quickly gained ground within the hemisphere of the Alemannian speaking areas like French Alsace, the Swiss Confederation, South West Germany, Western Austria and today’s North-East Italy (formely part of the Habsburg Austrian-Hongrian Empire). Though Bullinger did not leave Switzerland, he conducted an extended correspondence all over Europe and was so well informed that he edited a kind of newspaper about political developments. His controversies on the Lord's Supper with Luther, and his correspondence with Lelio Sozzini, exhibit, in different connections, are an admirable mixture of dignity and tenderness. With Calvin he concluded (1549) the Consensus Tigurinus on the Lord's Supper. The First Helvetic Confession (Latin: Confessio Helvetica prior), known also as the Second Confession of Basel, was drawn up at that city in 1536 by Bullinger and Leo Jud of Zürich, Megander of Bern, Oswald Myconius and Grynaeus of Basel, Bucer and Capito of Strasbourg, with other representatives from Schaffhausen, St Gall, Mülhausen and Biel. In order to overcome differences on the Lord’s Supper with Martin Luther in the interests of church unity. The first draft was in Latin and the Zürich delegates objected to its Lutheran phraseology. Leo Jud's German translation was, however, accepted by all, and after Myconius and Grynaeus had modified the Latin form, both versions were welcomed to and adopted on February 26, 1536. Bullinger played a crucial role in the drafting of the Second Helvetic Confession of 1566. What eventually became the Second Helvetic Confession originated in a personal statement of his faith which Bullinger intended to be presented to the Zurich Council upon his death. In 1566, when the elector palatine introduced Reformed elements into the church in his region, Bullinger felt that this statement might be useful for the elector, so he had it circulated among the Protestant cities of Switzerland who signed to indicate their assent. Later, the Reformed churches of France, Scotland, and Hungary would do likewise. The Second Helvetic Confession (Latin: Confessio Helvetica posterior) was written by Bullinger in 1562 and revised in 1564 as a private exercise. It came to the notice of the elector palatine Frederick III, who had it translated into German and published. The Second Helvetic Confession gained a favourable hold among the Swiss churches, who had found the First Confession too short and too Lutheran. It was adopted by the Reformed Church not only throughout Switzerland but in Scotland (1566), Hungary (1567), France (1571), Poland (1578), Bohemia31 and was used as pretext for what later became known as the Heidelberg Catechism and therefore belongs to the most generally recognized Confession of the Reformed Church. The Second Helvetic Confession accepted the “Ever Virgin” notion from John Calvin, which spread throughout much of Europe with the approbation of this document in the

above mentioned countries.

The French Confession de Foy, the Scottish Confessio Fidei(1560), the Belgian Ecclasiarum Belgicarum Confessio(1566), and the Heidelberg Catechism(1563), Canons of Dordt (1619), Westminster Confession of Faith (1646)33, Westminster Shorter Catechism (1649),Westminster Larger Catechism (1649) all include references to the Virgin Birth, mentioning specifically, that Jesus was born without the participation of a man. Invocations to Mary were not tolerated however, in light of Calvin’s position, that any prayer to saints in front of an altar is prohibited.

4.2 History of Calvinist Confession Creeds in the 16th/ 17th Century

The Reformed movement then spread to Germany. The city of Heidelberg, where the Heidelberg Catechism originated, became an influential center of Reformed thinking. Nonetheless, much of Germany remained staunchly Lutheran. A minority of Lutherans in Germany were affected by Calvin’s thinking, most notably Philip Melanchton (1497–1560), a close associate of Luther who was unkindly referred to by his peers as a crypto-Calvinist. 34 Eventually, a number of Melanchton’s followers, estranged from the Lutherans after Luther’s death, joined the Reformed Church in Germany.

Calvinism also took hold in Hungary, 35 Poland , and the Low Countries, particularly the Netherlands, where it penetrated the southern regions about 1545 and the northern about 1560. From the start, the Calvinist movement in the Netherlands was more influential than its number of adherents might suggest. But Dutch Calvinism did not flower profusely until the seventeenth century, cultivated by the famous international Synod of Dort in 1618–1619 and fortified by the Dutch Further Reformation (De Nadere Reformatie), a primarily seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century movement paralleling English Puritanism. The Dutch Further Reformation

dates from such early representatives as Jean Taffin (1528–1602)38 and Willem Teellinck (1579–1629), and extends to Alexander Comrie (1706–1774).

The Reformed movement also made substantial inroads into France. By the time Calvin died in 1564, 20 percent of the French population—some two million people—confessed the Reformed faith. In fact, this 20 percent included half of the aristocracy and middle class in France.

For a while, it seemed that France might officially embrace the Reformed faith. But Roman Catholic persecution and civil war halted the spread of Reformed teaching. In some ways, the French Reformed movement has never recovered from this blow of persecution and attack in the sixteenth century. On the other hand, God brought good out of evil—the Reformed believers who fled France, known as the Huguenots, injected fresh spiritual vitality and zeal into the Reformed movement everywhere they settled. The Reformation spread rapidly to Scotland, largely under the leadership of John Knox (1513–1572), who served nineteen months as a galley slave before he went to England and then to Geneva. Knox brought the Reformation’s principles from Geneva to Scotland and there became its most notable spokesman.41 In 1560, the Scottish Parliament rejected papal authority, and the following year, the Scottish Reformed “Kirk,” or church, was reorganized. In ensuing generations, many Scots became stalwart Calvinists, as did many of the Irish and the Welsh.

In England, Henry VIII (1491–1547) rebelled against papal rule so that he could legally divorce, remarry, and hopefully produce a male heir. He tolerated a mild reformation but established himself as the Church of England’s supreme head, even as he remained essentially

Roman Catholic in his theology. 42 During the short reign of his young son Edward VI (1547–1553), who, together with his council, had a great heart for true reformation, some gains were made, especially by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer (1489–1556) through his book Homilies, his Book of Common Prayer, and his Forty-Two Articles of Religion. All of this seemed to be

reversed during the bloody reign of Mary Tudor (1553–1558), who reinstated the Latin Mass and enforced papal allegiance at the cost of nearly three hundred Protestant lives. But the blood of those martyrs, including Cranmer, was to be the seed of the Protestant cause in England.

When Mary’s half-sister Elizabeth (1533–1603) succeeded her, many Protestants harbored fervent hopes that the reforms begun under Edward VI would grow exponentially. Elizabeth, however, was content with the climate of British Protestantism and strove to subdue dissident voices. Those who fought too much for reform in matters of worship, godliness, politics, and culture were persecuted and deprived of their livings. Elizabeth’s cautious, moderate type of reform disappointed many and eventually gave rise to a more thorough and robust Calvinism that was derogatorily called Puritanism.

Puritanism lasted from the 1560s to the early 1700s. The Puritans believed the Church of England had not gone far enough in its reformation, because its worship and government did not agree fully with the pattern found in Scripture. They called for the pure preaching of God’s Word; for purity of worship as God commands in Scripture; and for purity of church government, replacing

the rule of bishops with Presbyterianism. Above all, they called for greater purity or holiness of life among Christians. As J. I. Packer has said, “Puritanism was an evangelical holiness movement seeking to implement its vision of spiritual renewal, national and personal, in the

church, the state, and the home; in education, evangelism, and economics; in individual discipleship and devotion, and in pastoral care and competence.”

Doctrinally, Puritanism was a kind of vigorous Calvinism; experientially, it was warm and contagious; evangelistically, it was aggressive, yet tender; ecclesiastically, it was theocentric and worshipful; and politically, it sought to make the relations between king, Parliament, and subjects scriptural, balanced, and bound by conscience.

Presbyterians, Episcopalians, and Congregationalists were all part of the Calvinist movement. Some Puritans seceded from the Church of England during the reign of King James I (1603–1625). They became known as separatists or dissenters and usually formed

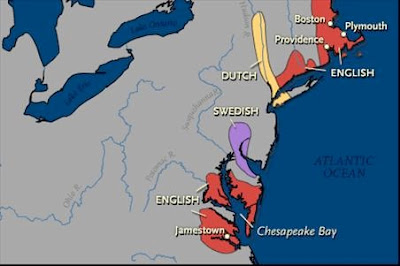

Congregationalist churches. Puritan conformists remained within the Anglican fold. Eventually, Calvinism crossed the Atlantic to the British colonies in North America, where the New England Puritans took the lead in expounding Reformed theology and in founding

ecclesiastical, educational, and political institutions. 45 The Puritans who settled in the Massachusetts Bay Colony continued to sanction the Church of England to some degree, whereas the Pilgrims who sailed to America in the Mayflower and settled in Plymouth (1620) were separatists.46 Despite these differences, all Puritans were zealous Calvinists. As John Gerstner observes, “ New England, from the founding of Plymouth in 1620 to the end of the 18th century, was predominantly Calvinistic.” Four more streams of immigrants brought Calvinism to America. Dutch Reformed believers, from the 1620s, were responsible for the settlement of New Netherlands, later called New York.

The French Huguenots arrived by the thousands in New York, Virginia, and the Carolinas in the late seventeenth century. From 1690 to 1777, more than two hundred thousand Germans, many of whom were Reformed, settled mostly in the Middle Colonies. The final stream was the Scots and the Scotch-Irish, all Presbyterians. Some settled in New England, but many more poured into New York, Pennsylvania, and the Carolinas. “As a consequence of this extensive immigration and internal growth it is estimated that of the total population of three million in this country in 1776, two-thirds of them were at least nominally Calvinistic,” John Bratt concludes. “At the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, the largest denominations were, in order:

Congregationalists, Anglicans, Presbyterians, Baptists, Lutherans, German Reformed, and Dutch Reformed. Roman Catholicism was tenth and Methodism was twelfth in size.” With the exception of the migrations to America, all of this spreading of the Reformed faith happened by the end of the sixteenth century.49 The most extensive and enduring strongholds of the Reformed movement became the Netherlands, Germany, Hungary, Great Britain, and North America.

It is noteworthy that all of these Reformed bodies shared the conviction that Christianity in many parts of Europe prior to the Reformation was little more than a veneer. As these Reformed believers surveyed Europe, they saw what they could regard only as large swaths of paganism.

The planting of solidly biblical churches was desperately needed. This explains in large measure the Reformers’ missionary focus on Europe. After chosing three different types of church governing over time, the Reformed movement developed into two very similar systems of theology: the Continental Reformed and in British-American Presbyterian church model. The Continental Reformed Church Governing models are represented in in the confessions creed of the 1st and the 2nd Helvetic Confession in Switzerland, the Anabaptist Schleitheim Confession, the Confession du Foy in France, the Belgic Confession, the Heidelberg Catechism, in Germany and the Canons of Dortrecht in the Netherlands. The British-American Presbyerian model was expressed in the Westminster standards—the Westminster Confession of Faith, the Larger Catechism, and the Shorter Catechism. These two systems were not opposed to each other. But it was not the end of new models either. British Puritans profoundly influenced the Dutch Further Reformation in the seventeenth century, the Italian-Swiss theologian Francis Turretin (1623–1687) profoundly affected American Presbyterianism.50 Turretin’s systematic theology was taught at Princeton Seminary until the 1870s, only then it was replaced by that of Charles Hodge.

No comments:

Post a Comment